The State of the High Street: A Deep-Dive Report

Fashion editor and writer Emma McCarthy explores how the great British high street has changed over the last few decades, as well as what's to come in the future.

What does the British high street need to survive? It’s a thoroughly modern conundrum; a wander down any town’s high street or local shopping centre will confirm that retail has had a particularly tough time of late. Decades of decline, rapidly accelerated by the global pandemic, have resulted in shuttered shop fronts and disappearing household names, leaving once-thriving communities reduced to shadows of their former selves.

Where fashion is concerned, the issue is more nuanced. Increasingly, a digitally native and social media-influenced consumer prefers to shop whilst they scroll, but this reduction in footfall to physical retailers is only part of the problem. The well-established modus operandi of many high-street brands—stack it high and sell it cheap—has resulted in what can often seem like a shopping culture of limitless options but a lack of genuine choice; an endless supply of repetitive designs available at multiple carbon-copy retailers. It’s little wonder many jaded fashion fans have turned to secondhand shopping instead; a new study reveals that the global fashion resale market is expected to grow to $360 billion by 2030.

The pre-loved boom would support the theory that younger consumers are increasingly aware of the environmental footprint of fashion, which creates a challenge for retailers who have failed to adapt to the demands of more sustainable practices. But the rampant growth of super-low-cost, ultra-fast fashion juggernauts such as Shein, which caters to consumers who value speed and affordability over all else, would suggest that ethics may not strictly align with the dominant consumer habits.

Just last month, Zara owner Inditex SA announced plans to launch its budget-friendly sister chain Lefties into the UK next year in a bid to rival current market leader Primark, which makes business sense in an economy plagued by a cost-of-living crisis, where many don’t have the luxury of making the most eco-friendly choice. Some critics believe that the quality of more affordable garments has taken a hit as a result, arguing that a decline in quality of our high-street brands is an unavoidable consequence of this changing landscape and the economic pressures faced by retailers. They should be pleased to hear, then, that there’s a sure show of defiance coming through amongst the more resilient retailers, via glossy store revamps, rebrands and major creative appointments.

H&M Group-owned & Other Stories appointed former London Fashion Week favourite and ex-Diane von Furstenberg chief creative officer Jonathan Saunders to the same role earlier this year, whilst American fashion designer Zac Posen, who shuttered his namesake luxury line in 2019, has been installed as the creative director of Gap since February 2024, overseeing all elements of brand direction, as well as designing GapStudio, a new line intended as an elevated take on Gap classics at a more premium price point.

In September last year, Uniqlo recruited British designer Clare Waight Keller, who hails from the ateliers of Paris, having previously headed up the luxury labels Givenchy and Chloé as its new creative director. The Japanese basics brand is no stranger to recruiting esteemed designers to its workforce, having continued its successful collaboration with design duo Christophe Lemaire and Sarah-Linh Tra of cult Paris-based label Lemaire for over a decade, and Jonathan Anderson (who recently debuted at Dior) since 2017.

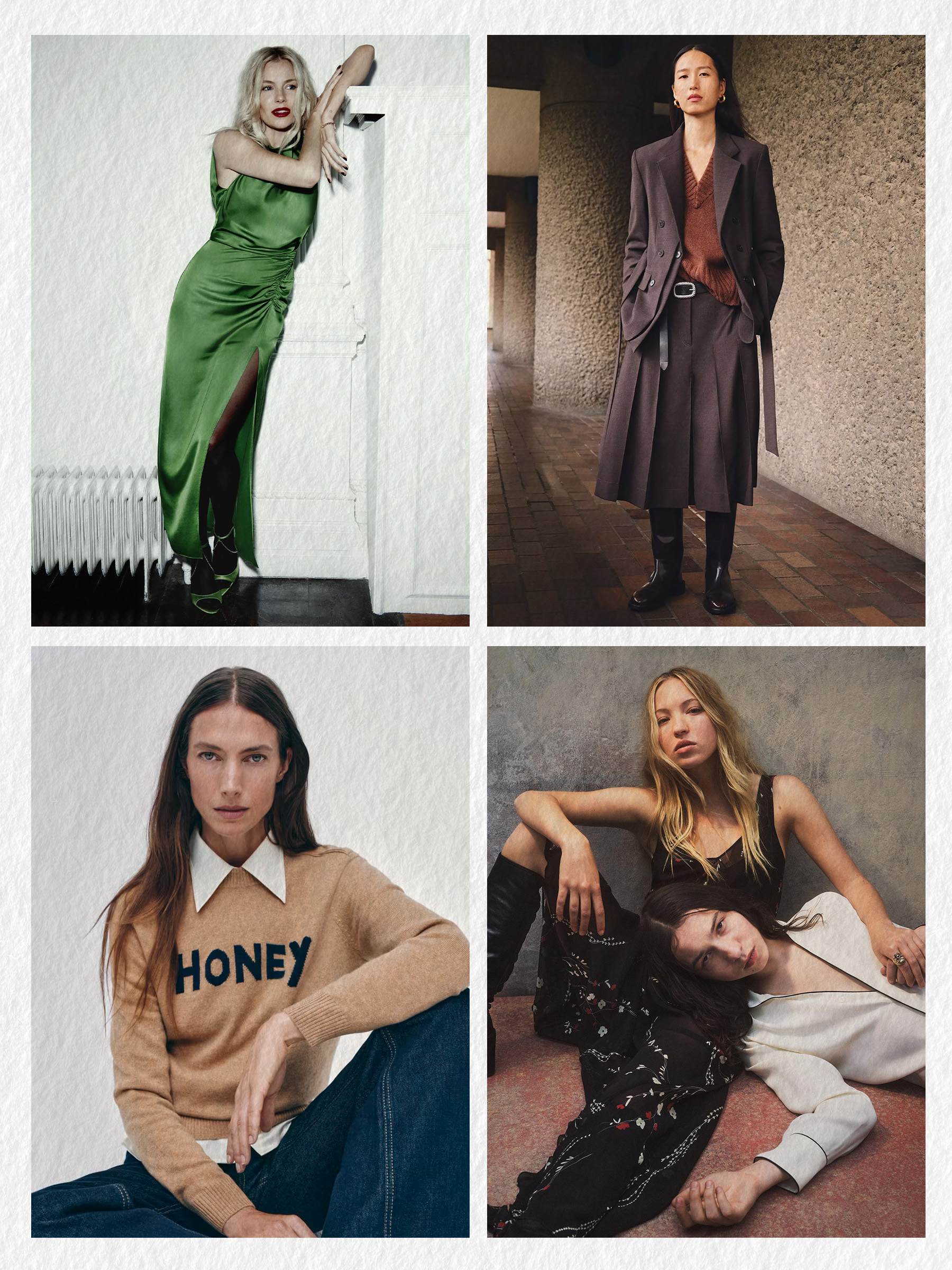

Clare Waight Keller, Creative Director of Uniqlo; Zac Posen, Creative Director of GAP with Laura Harrier in custom GAP for the 2024 Met Gala; Jonathan Sanders, Chief Creative Office of & Other Stories; Tabitha Simmons collaboration with NEXT

The idea that luxury and value can co-exist is one which kicked off on the high street through designer-brand collaborations. Who could forget the iconic Kate Moss X Topshop collections (from 2007 to 2010), or Karl Lagerfeld for H&M in 2011? Such high-low dream teams have been less prevalent in recent years, but the concept has recently been revived with the likes of Victoria Beckham X Mango and Bella Freud X Marks and Spencer.

Currently, it seems that the more unexpected hook-ups are also often the most successful. John Lewis is banking on London’s most hyped labels, including Rejina Pyo and A.W.A.K.E Mode, to bolster its premium fashion offering, whilst Next has also dipped a toe into the high-street-meets-high-fashion market with its first capsule collection with shoe designer and notable stylist Tabitha Simmons. Meanwhile, British institution M&S has now launched another boho-chic collection designed with fashion icon Sienna Miller, following the success of the first.

But whilst limited-edition capsule collections designed in tandem with aspirational names will generate buzz and sales, retailers must also nurture and sustain long-term strategies if they hope to future-proof. After all, the success of a high-street brand is not to be measured in its starry collaborations that come and go, but in its bread-and-butter collections.

For example, the likes of minimalist-fashion staple COS and wardrobe-essentials favourite Arket—both owned by Swedish H&M Group—are now relied upon to offer sleek basics and timeless classics over seasonal trends at a relatively accessible price point, whilst Reiss offers excellent tailoring, and has long been filling the gap between luxury and high street where workwear is concerned. And then there are the more directional, slightly higher-price-point brands that have emerged in recent years, and are as applauded for their designs as they are for their quality; names like Aligne, Whistles and Reformation.

Sienna Miller for M&S; Rejina Pyo for John Lewis; Bella Freud for M&S; Kate Moss for Zara

With a 141-year heritage, M&S has fought a hard-won battle to return to fashion relevance. The retailer’s most recent financial results revealed a 22% rise in pre-tax profits in the year, with overall sales up 6% to £13.9bn, and fashion and homeware increasing 3.5% to £4.2bn. The sudden revitalisation of the high-street stalwart is no coincidence, rather largely the work of womenswear director Maddy Evans, who joined in 2019 when sales were plummeting and the brand fell off the FTSE 100 for the first time, owing to what then-chief executive Steve Rowe admitted was due to a reputation for “frumpiness”. Now, having honed an expertise for creating high-quality, trend-influenced pieces and viral hits, not to mention continuing its long-standing commitment to offering an extended range of sizing (something which has improved but is still overall lacking on the high street), the retailer has found favour with a new crowd of younger millenials, Gen Z and TikTok influencers asking the question, “Am I just old now, or has M&S always been this good?!”

Undoubtedly, the lightning-fast advancement of technology means that the role of brick-and-mortar shops is no longer merely as a place to buy things. Topshop was amongst the first high-street retailers to pioneer the concept store. Throughout the noughties, the brand’s behemoth Oxford Circus flagship was a mecca for young consumers, attracting an average of 28,000 shoppers every day, who could happily while away entire weekends flitting between the in-store DJ booth, piercing parlour, nail salon and changing rooms. After collapsing into administration in 2021, this year marked a much-publicised comeback of the once-cult brand. Keen to capitalise on the nostalgia felt by millennials who mourned its disappearance, the rebrand included a campaign with former poster girl Cara Delevingne and a star-studded runway show in London’s Trafalgar Square—a nod to the brand’s legacy as the first high-street brand on the London Fashion Week schedule.

One key difference is that the retailer, now owned by ASOS, won’t be reopening its landmark standalone flagship (which is now an IKEA). Instead, Topshop announced it would be expanding its physical retail footprint nationwide with a partnership with department store John Lewis. Granted, it’s a dilution of experiential retail in its heyday, but it just might bring back some of the feeling of Old Topshop. Because beyond the ability to touch and try on clothes, the real magic of Old Topshop resided in its role as a sort of community hub where you could meet friends, have a browse or a blow-dry and perhaps buy a new going-out top for the weekend.

We’re overdue a renaissance of the buzzy IRL retail. Certainly, there’s evidence to support that the appetite is still there: last month, high-street fashion stores saw a significant 6.9% rise in sales—a marked improvement over online fashion sales, which grew by just 2.3%. Looking to the future, hybrid retail models that manage to seamlessly integrate online and offline experiences (clicks and mortar?) will prove essential in appealing to a generation that connects to the world via phone screens, whilst in-store events can create an opportunity for both human connection and impact on social media. Exclusive merchandise and personalised services only accessible by visiting a store can also encourage footfall. In recent years, we’ve seen some retailers introducing secondhand and vintage pop-ups within their shops to reflect the growing trend of consumers who like to shop unique vintage pieces alongside their new-season items.

As we’ve witnessed from the closure of brick-and-mortar shops of brands including Oasis, House of Fraser and Debenhams and the continued struggles faced by the likes of Ted Baker and River Island, a strong identity and USP are essential to maintaining relevance in an overcrowded market. What’s certain is that not all will survive the new era, though perhaps that’s not necessarily a bad thing. Maybe what the high street needs to survive is not a revival, but a reset. Now, more than ever, the message is clear: adapt or fold.